Router Design and Algorithms (Part 2) ↩

Why We Need Packet Classification?

As the Internet becomes increasingly complex, networks require quality of service guarantees and security guarantees for their traffic. Packet forwarding based on the longest prefix matching of destination IP addresses is not enough and we need to handle packets based on multiple criteria (TCP flags, source addresses) - we refer to this finer packet handling as packet classification.

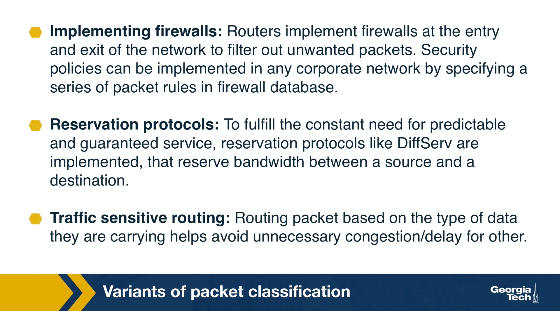

Variants of packet classification are already established:

-

Firewalls: Routers implement firewalls at the entry and exit points of the network to filter out unwanted traffic, or to enforce other security policies.

-

Resource reservation protocols: For example, DiffServ has been used to reserve bandwidth between a source and a destination.

-

Routing based on traffic type: Routing based on the specific type of traffic helps avoid delays for time-sensitive applications.

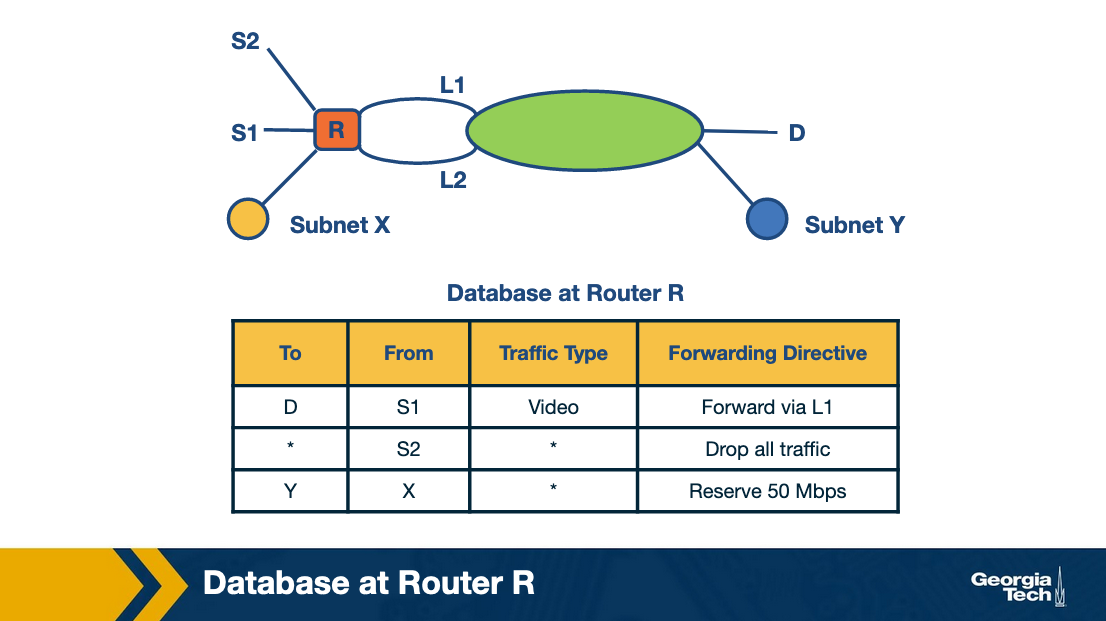

Example for traffic type sensitive routing:

The above figure shows an example topology where networks are connected through router R. Destinations are shown as S1, S2, X, Y and D. L1 and L2 denote specific connection points for router R. The table shows some example packet classification rules. The first rule is for routing video traffic from S1 to D via L1. The second rule drops all traffic from S2, for example, in the scenario that S2 was an experimental site. The third rule reserves 50 Mbps of traffic from prefix X to prefix Y, which is an example of rule for resource reservation.

Packet Classification: Simple Solutions

Before looking into algorithmic solutions to the packet classification problem, let’s take a look at simplest approaches that we have:

Linear Search

Firewall implementations perform a linear search of the rules database and keep track of the best-match rule. This solution can be reasonable for a few rules but the time to search through a large database that may have thousands of rules can be prohibitive.

Caching

Another approach is to cache the results so that future searches can run faster. This has two problems:

-

The cache-hit rate can be high (eg 80-90%), but still we will need to perform searches for missed hits.

-

Even with a high 90% hit rate cache, a slow linear search of the rule space will result in poor performance. For example, suppose that a search of the cache costs 100 nsec (one memory access) and that a linear search of 10,000 rules costs 1,000,000 nsec = 1 msec (one memory access per rule). Then the average search time with a cache hit rate of 90% is still 0.1 msec, which is rather slow.

Passing Labels

The Multiprotocol Label Switching (MPLS) and DiffServ use this technology. MPLS is useful for traffic engineering. A label-switched path is set up between the two sites A and B. Before traffic leaves site A, a router does packet classification and maps the web traffic into an MPLS header. Then the intermediate routers between A and B apply the label without having to redo packet classification. DiffServ follows a similar approach, applying packet classification at the edges to mark packets for special quality of service.

Scheduling and Head of Line Blocking

In this topic, we start discussing about the problem of scheduling.

Scheduling

Let’s assume that we have an NxN crossbar switch, with N input lines, N output lines, and N2 crosspoints. Each crosspoint needs to be controlled (on/off), and we need to make sure that each input link is connected with at most one output link. Also, for better performance we want to maximize the number of input/output links pairs that communicate in parallel.

Take the ticket algorithm

A simple scheduling algorithm is the “take the ticket algorithm”. Each output line maintains a distributed queue for all input lines that want to send packets to it. When an input line wants to send a packet to a specific output line, it requests a ticket. The input line waits for the ticket to be served. At that point, the input line connects to the output line, the crosspoint is turned on, and the input line sends the packet.

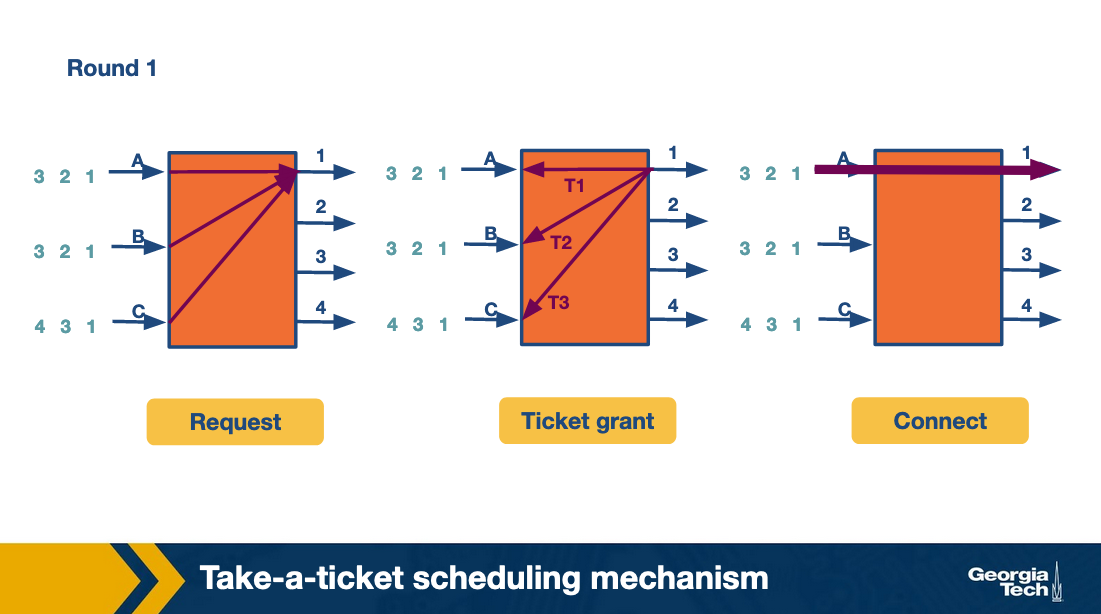

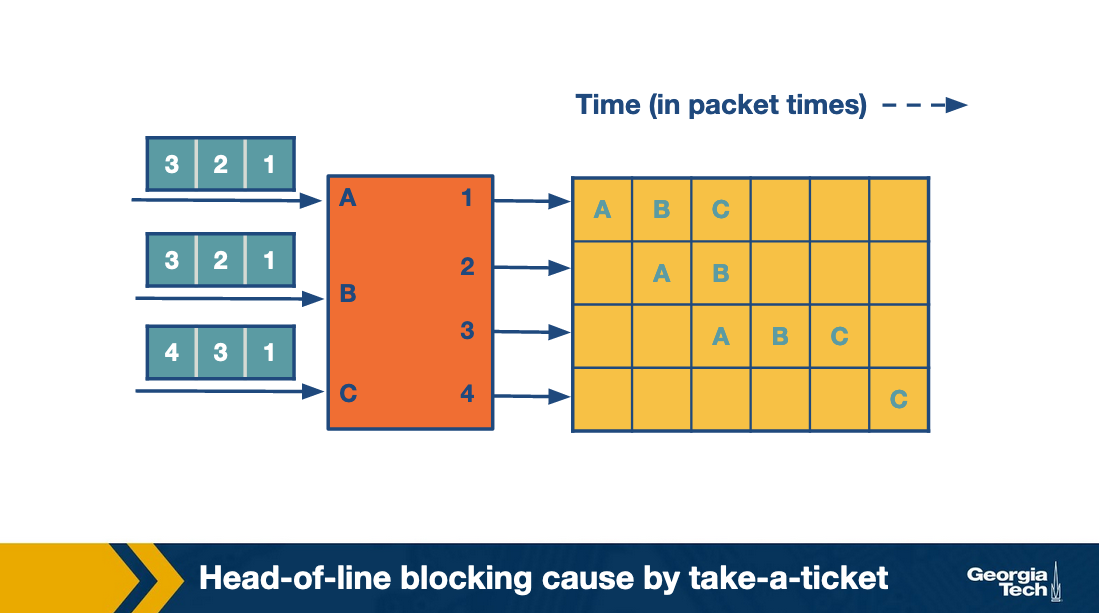

As an example, let’s consider the figure below that shows three input lines which want to connect to four output lines. Next to each input line, we see the queue of the output lines it wants to connect with. For example, input lines A and B want to connect with output lines 1,2,3.

At the first round, the input lines make ticket requests. For example line A requests a ticket for link1. The same for B and C. So output link 1 grants three tickets, and it will process them in order. First the ticket for A, then for B and then for C. Input A observes that its ticket is served, so it connects to output link 1 and sends the packet.

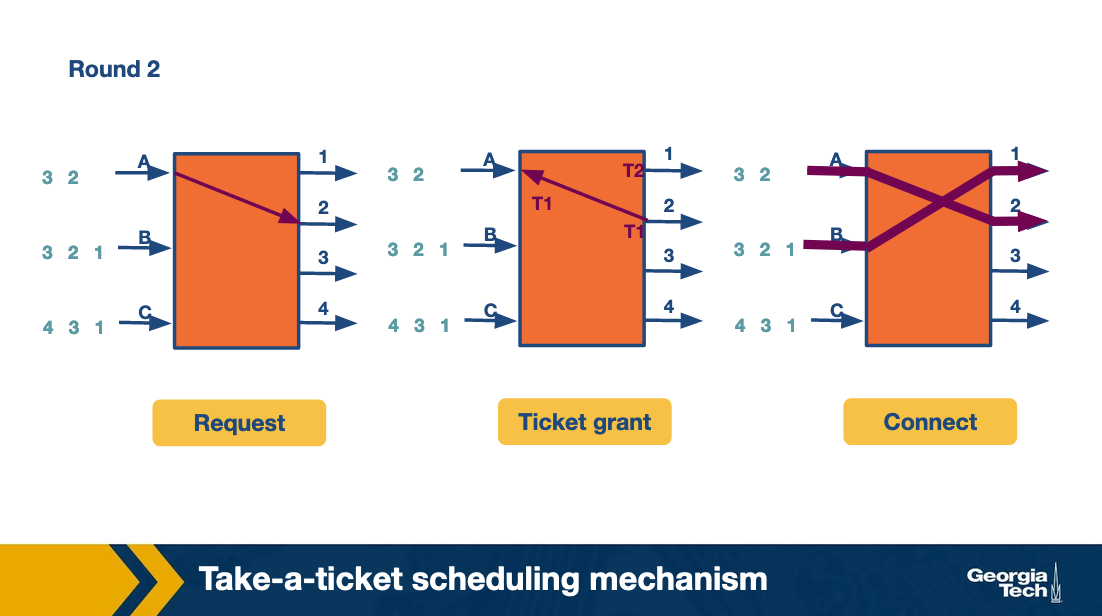

At the second round, A repeats the process to request a ticket and connect with link 2. Also B requests a ticket and connects with link 2.

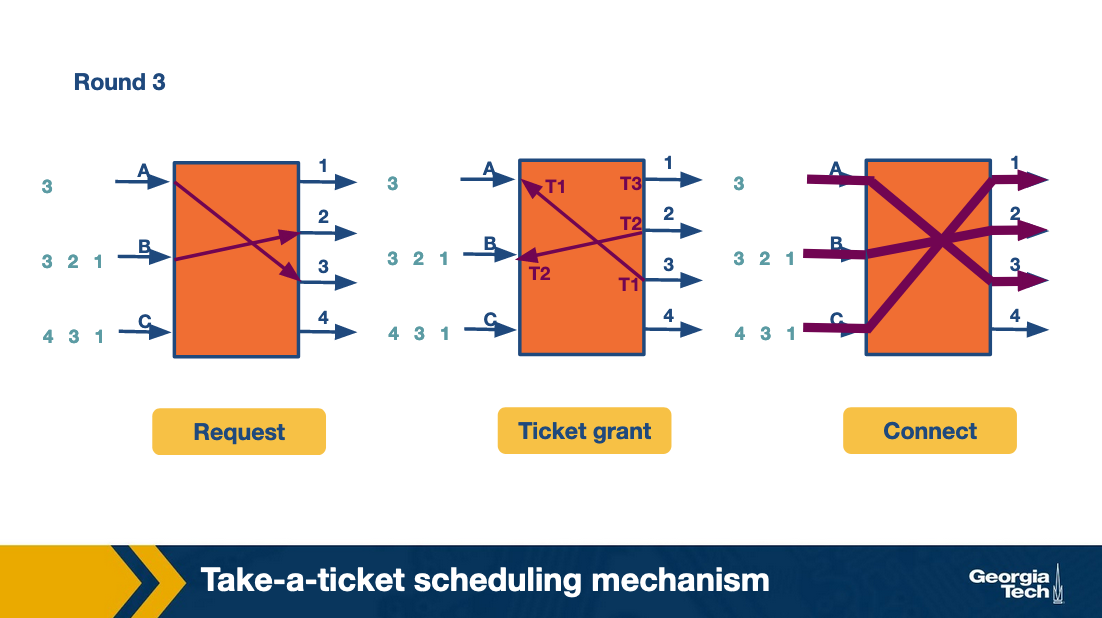

At the third round, A and B move forward repeating the steps for their next connection. C gets the chance to make its first request and connect with output link 1. All this time C was blocked waiting for A and B.

The following figure, which shows how the entire process progresses. For each output link we can see the time line as it connects with input links. The empty spots mean there was no packet send at the corresponding time.

As we see, in the first iteration while A sends its packet, the entire queue for B and C are waiting. We refer to this problem as head-of-line (HOL) blocking because the entire queue is blocked by the progress of the head of the queue.

Avoiding Head of Line Blocking

Avoiding head-of-line blocking via output queuing:

Suppose that we have an NxN crossbar switch. Can we send the packet to an output link without queueing? If we could, then assuming that a packet arrives at an output link, it can only block packets that are sent to the same output link. We could achieve that, if we have the fabric running N times faster than the input links.

A practical implementation of this approach is the Knockout scheme. It relies on breaking up packets into fixed size (cell). We suppose that in practice the same output rarely receives N cells and the expected number is k (smaller than N). Then we can have the fabric running k times as fast as an input link, instead of N. We may still have scenarios where the expected case is violated. To accommodate these scenarios, we have one or more of a primitive switching element that randomly picks the chosen output:

- k = 1 and N = 2. Randomly pick the output that is chosen. The switching element in this case is called a concentrator.

- k = 1 and N > 2. One output is chosen out of N possible outputs. In this case, we can use the same strategy of multiple 2-by-2 concentrators.

- k needs to be chosen out of N possible cells, with k and N arbitrary values. We create k knockout trees to calculate the first k winners. The drawback with this approach is that is it is complex to implement.