Software Defined Networking (Part 1) ↩

What led us to SDN?

Software Defined Networking (SDN) arose as part of the process to make computer networks more programmable. Computer networks are very complex and especially difficult to manage for two main reasons:

Diversity of equipment on the network

- Proprietary technologies for the equipment

- Diversity of equipment

Computer networks have a wide range of equipment - from routers and switches to middleboxes such as firewalls, network address translators, server load balancers, and intrusion detection systems (IDSs). The network has to handle different software adhering to different protocols for each of these equipment. Even with a network management tool offering a central point of access, they still have to operate at a level of individual protocols, mechanisms and configuration interfaces, making network management very complex.

Control and data plane separation

Why Separate the Data Plane from the Control Plane?

Why separate the control from the data plane?

We know that SDN differentiates from traditional approaches by separating the control and data planes.

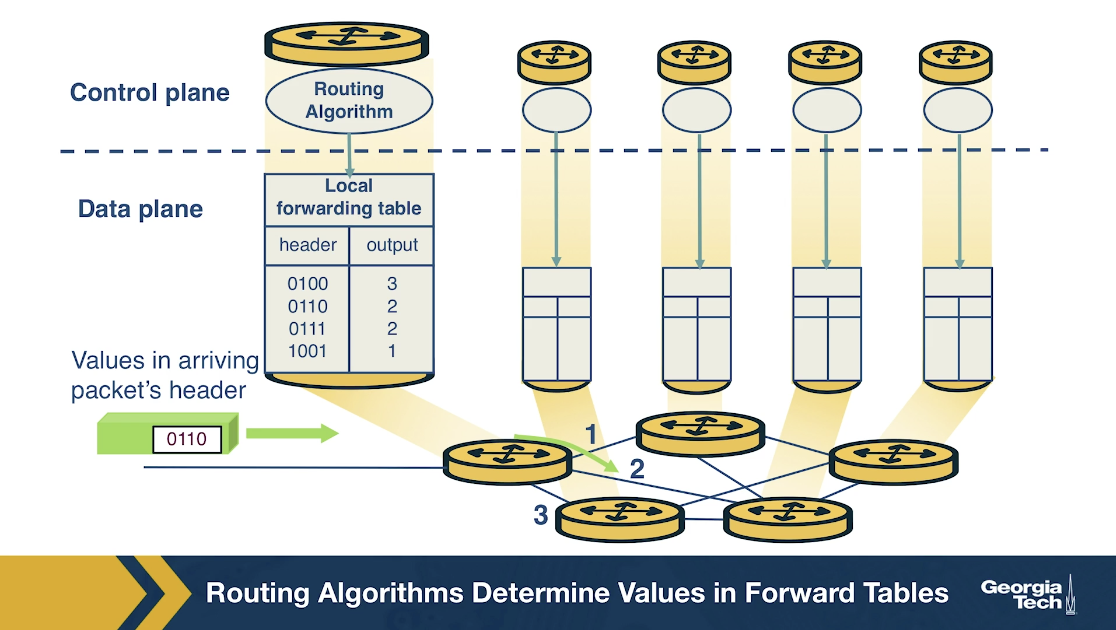

The control plane contains the logic that controls the forwarding behavior of routers such as routing protocols and network middlebox configurations. The data plane performs the actual forwarding as dictated by the control plane. For example, IP forwarding and Layer 2 switching are functions of the data plane.

The reasons we separate the two are:

-

Independent evolution and development

In the traditional approach, routers are responsible for both routing and forwarding functionalities. This meant that a change to either of the functions would require an upgrade of hardware. In this new approach, routers only focus on forwarding. Thus, innovation in this design can proceed independently of other routing considerations. Similarly, improvement in routing algorithms can take place without affecting any of the existing routers. By limiting the interplay between these two functions, we can develop them more easily.

-

Control from high-level software program

In SDN, we use software to compute the forwarding tables. Thus, we can easily use higher-order programs to control the routers’ behavior. The decoupling of functions makes debugging and checking the behavior of the network easier.

Separation of the control and data planes supports the independent evolution and development of both. Thus, the software aspect of the network can evolve independent of the hardware aspect. Since both control and forwarding behavior are separate, this enables us to use higher-level software programs for control. This makes it easier to debug and check the network’s behavior.

In addition, this separation leads to opportunities in different areas.

-

Data centers. Consider large data centers with thousands of servers and VMs. Management of such large network is not easy. SDN helps to make network management easier.

-

Routing. The interdomain routing protocol used today, BGP, constrains routes. There are limited controls over inbound and outbound traffic. There is a set procedure that needs to be followed for route selection. Additionally, it is hard to make routing decisions using multiple criteria. With SDN, it is easier to update the router’s state, and SDN can provide more control over path selection.

-

Enterprise networks. SDN can improve the security applications for enterprise networks. For example, using SDN it is easier to protect a network from volumetric attacks such as DDoS, if we drop the attack traffic at strategic locations of the network.

-

Research networks. SDN allows research networks to coexist with production networks.

Control Plane and Data Plane Separation

Two important functions of the network layer are:

Forwarding

Forwarding is one of the most common, yet important functions of the network layer. When a router receives a packet at its input link, it must determine which output link that packet should be sent through. This process is called forwarding. It could also entail blocking a packet from exiting the router, if it is suspected to have been sent by a malicious router. It could also duplicate the packet and send it along multiple output links. Since forwarding is a local function for routers, it usually takes place in nanoseconds and is implemented in the hardware itself. Forwarding is a function of the data plane.

So, a router looks at the header of an incoming packet and consults the forwarding table, to determine the outgoing link to send the packet to.

Routing

Routing involves determining the path from the sender to the receiver across the network. Routers rely on routing algorithms for this purpose. It is an end-to-end process for networks. It usually takes place in seconds and is implemented in the software. Routing is a function of the control plane.

In the traditional approach, the routing algorithms (control plane) and forwarding function (data plane) are closely coupled. The router runs and participates in the routing algorithms. From there it is able to construct the forwarding table which consults it for the forwarding function.

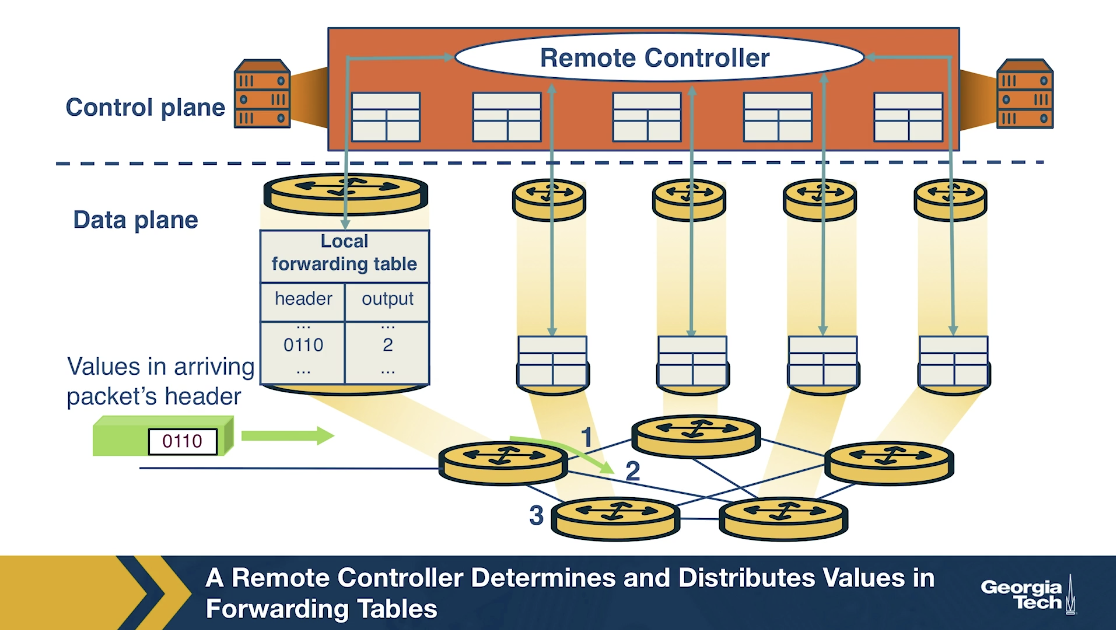

In the SDN approach, on the other hand, there is a remote controller that computes and distributes the forwarding tables to be used by every router. This controller is physically separate from the router. It could be located in some remote data center, managed by the ISP or some other third party.

We have a separation of the functionalities. The routers are solely responsible for forwarding, and the remote controllers are solely responsible for computing and distributing the forwarding tables. The controller is implemented in software, and therefore we say the network is software-defined.

These software implementations are also increasingly open and publicly available, which speeds up innovation in the field.

The SDN Architecture

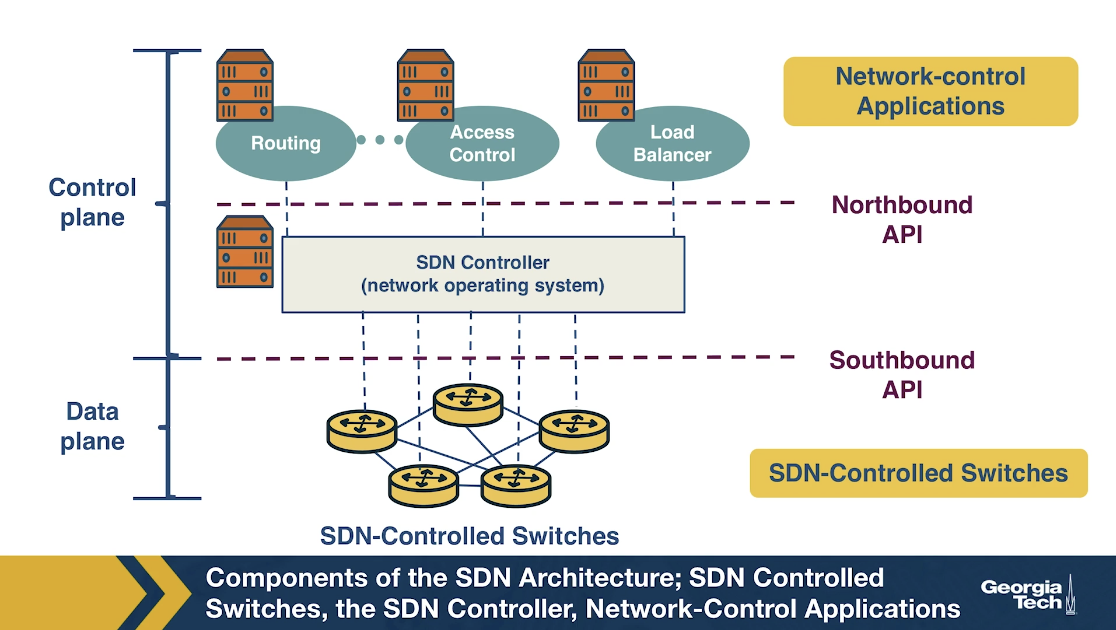

In the figure below we see the main components of an SDN network:

SDN-controlled network elements

The SDN-controlled network elements, sometimes called the infrastructure layer, is responsible for the forwarding of traffic in a network based on the rules computed by the SDN control plane.

SDN controller

The SDN controller is a logically centralized entity that acts as an interface between the network elements and the network-control applications.

Network-control applications

The network-control applications are programs that manage the underlying network by collecting information about the network elements with the help of SDN controller.

Let us now take a look at the four defining features in an SDN architecture:

- Flow-based forwarding: The rules for forwarding packets in the SDN-controlled switches can be computed based on any number of header field values in various layers such as the transport-layer, network-layer and link-layer. This differs from the traditional approach where only the destination IP address determines the forwarding of a packet. For example, OpenFlow allows up to 11 header field values to be considered.

- Separation of data plane and control plane: The SDN-controlled switches operate on the data plane and they only execute the rules in the flow tables. Those rules are computed, installed, and managed by software that runs on separate servers.

- Network control functions: The SDN control plane, (running on multiple servers for increased performance and availability) consists of two components: the controller and the network applications. The controller maintains up-to-date network state information about the network devices and elements (for example, hosts, switches, links) and provides it to the network-control applications. This information, in turn, is used by the applications to monitor and control the network devices.

- A programmable network: The network-control applications act as the “brain” of SDN control plane by managing the network. Example applications can include network management, traffic engineering, security, automation, analytics, etc. For example, we can have an application that determines the end-to-end path between sources and destinations in the network using Dijkstra’s algorithm.

<!–

<!–

The SDN Controller Architecture

The SDN controller is a part of the SDN control plane and acts as an interface between the network elements and the network-control applications.

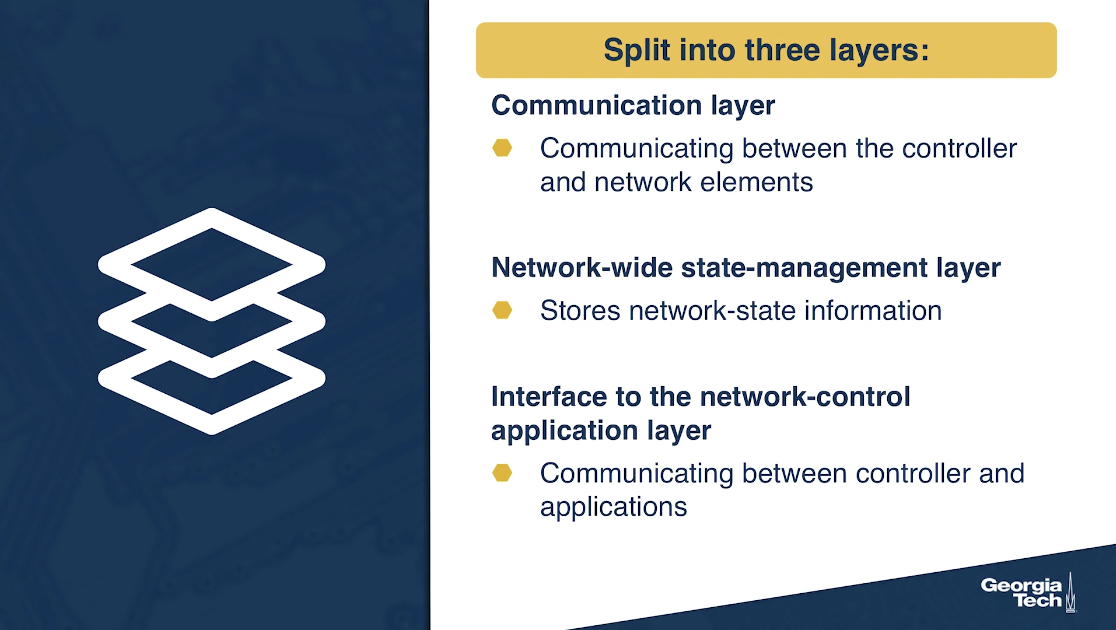

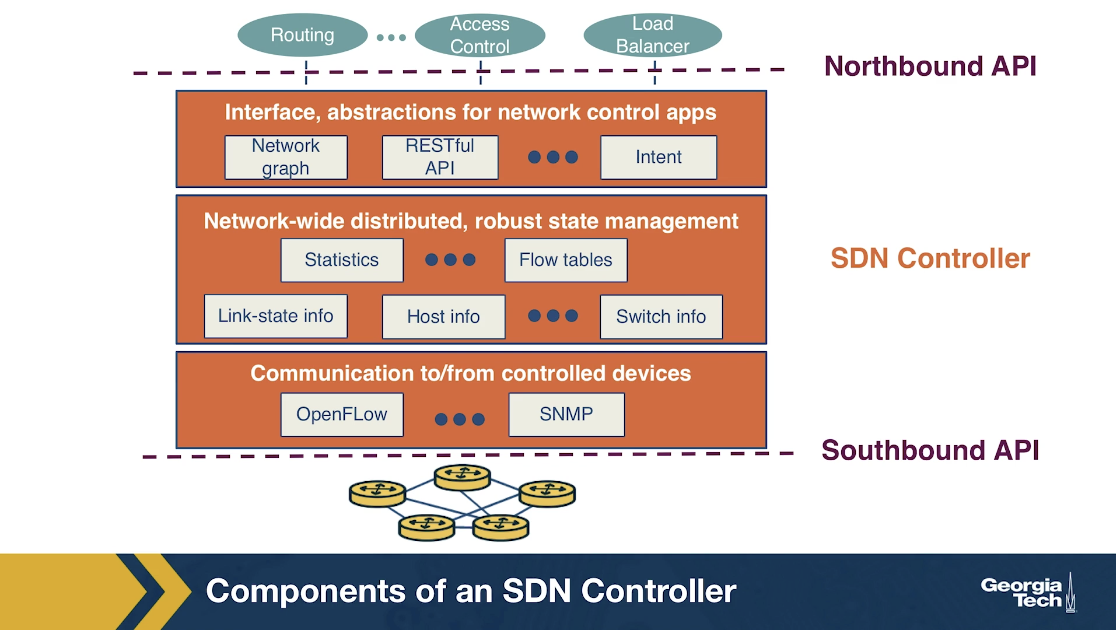

An SDN controller can be broadly split into three layers:

- Communication layer: communicating between the controller and the network elements

- Network-wide state-management layer: stores information of network-state

- Interface to the network-control application layer: communicating between controller and applications

Let’s look at each layer in detail starting from the bottom:

Communication Layer

This layer consists of a protocol through which the SDN controller and the network controlled elements communicate. Using this protocol, the devices send locally observed events to the SDN controller providing the controller with a current view of the network state. For example, these events can be a new device joining the network, heartbeat indicating the device is up, etc. The communication between SDN controller and the controlled devices is known as the “southbound” interface. OpenFlow is an example of this protocol, which is broadly used by SDN controllers today.

Network-wide state-management layer

This layer is about the network-state that is maintained by the controller. The network-state includes any information about the state of the hosts, links, switches and other controlled elements in the network. It also includes copies of the flow tables of the switches. Network-state information is needed by the SDN control plane to configure the flow tables.

Interface to the network-control application layer

This layer is also known as the controller’s “northbound” interface using which the SDN controller interacts with network-control applications. Network-control applications can read/write network state and flow tables in controller’s state-management layer. The SDN controller can notify applications of changes in the network state, based on the event notifications sent by the SDN-controlled devices. The applications can then take appropriate actions based on the event. A REST interface is an example of a northbound API.

The SDN controller, although viewed as a monolithic service by external devices and applications, is implemented by distributed servers to achieve fault tolerance, high availability and efficiency. Despite the issues of synchronization across servers, many modern controllers such as OpenDayLight and ONOS have solved it and prefer distributed controllers to provide highly scalable services.

OpenDayLight Architecture Overview

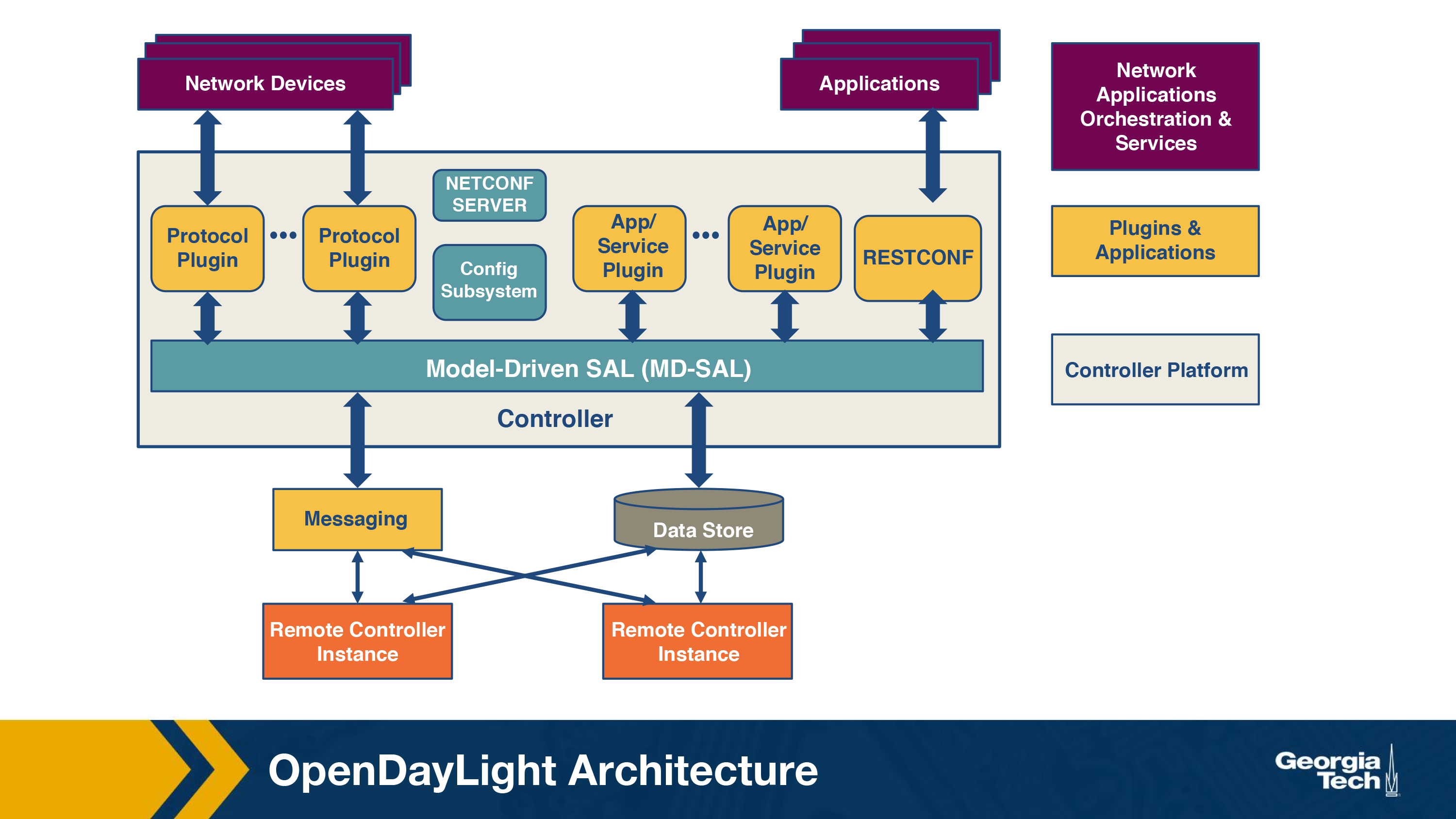

In the previous topics we looked at the SDN Controller architecture. We talked about the Southbound and Northbound interfaces, and how the SDN controller uses them to interact with other components.

In this topic, we will first take a look at the OpenDaylight controller architecture:

-

Southbound interface: This is used by the controller to communicate with network devices. The interface also allows support for various third-party vendor specific protocols like openflow, netflow, netconf etc. We can also write our own plugin in the Southbound interface.

-

Northbound interface: As the name suggests, it’s an “upward” bound interface so that SDN applications can talk to the controller platform underneath (see figure below). For eg an application to check connectivity of the network, the ping packets are sent to the Northbound interface to the controller, the controller parses information and will pass on the packets to the device interface via the Southbound API.

-

Model Driven Service Abstraction Layer (or MD-SAL): It is the abstraction layer provided by OpenStack for developers to add new features to the controller. Using karaf they can write services or protocol drivers to integrate them together. MDSAL has 2 components:

-

A shared datastore that has 2 tree based structures:

-

Config Datastore: This manages the representation of the network. It also does the sanity checking for any new services. For eg if you try to deploy a service to configure an interface, you use a chain of commands. This component manages how these changes are pushed.

-

Operation Datastore: This has the true representation of the network state based on data from the managed network elements. Once the final committed changes are reflected to the network devices, we save the data in this store.

-

-

A message bus that provides a way for various services and protocol drivers to notify and communicate with each other. –>

-

As IP networks grew in adoption worldwide, there were a few challenges that became more and more pronounced, such as:

- Handling the ever growing complexity and dynamic nature of networks: The implementation of network policies required changes right down to each individual network device, which were often carried out by vendor-specific commands and required manual configurations. This was a heavy upkeep for operators. Traditional IP networks are quite far away from achieving automatic response mechanisms to dynamic network environment changes.

- Tightly coupled architecture: The traditional IP networks consist of a control plane (handles network traffic) and a data plane (forwards traffic based on the control plane’s decisions) that are bundled together. They are contained inside networking devices, and are thus not flexible to work on. This is evidenced by the fact that any new protocol update takes as long as 10 years, because of the way these changes need to percolate down to every networking device that is a part of the IP network.

Software Defined Networking. This networking paradigm is an attempt to overcome limitations of the legacy IP networking paradigm. It starts by separating out the control logic (in the control plane) from the data plane. With this separation, the network switches simply perform the task of forwarding, and the control logic is purely implemented in a logically centralized controller (or a network OS), thereby making it possible for innovation to occur in areas of network reconfiguration and policy enforcement. Despite the centralized nature of control logic, in practice, production-level SDNs need a physically distributed control plane to achieve performance, reliability and scalability.

The separation of control and data plane is achieved by using a programming interface between the SDN controller and the switches. The SDN controller controls the data plane elements via the API. An example of such an API is OpenFlow. A switch in OpenFlow has one or more tables for packet handling rules. Each rule matches a subset of network traffic and performs actions such as dropping, forwarding, modifying etc. An OpenFlow switch can be instructed by the controller to behave like a firewall, switch, router, or even perform other roles like load balancer, traffic shaper, etc.

As opposed to traditional IP networks, SDN principles allow for a separation of concerns introduced between the definition of networking policies, their implementation in hardware, and the forwarding of traffic. It is this separation that allows for networking control problems to be viewed as tractable pieces, allowing for newer networking abstractions and simplifying networking management, allowing innovation.

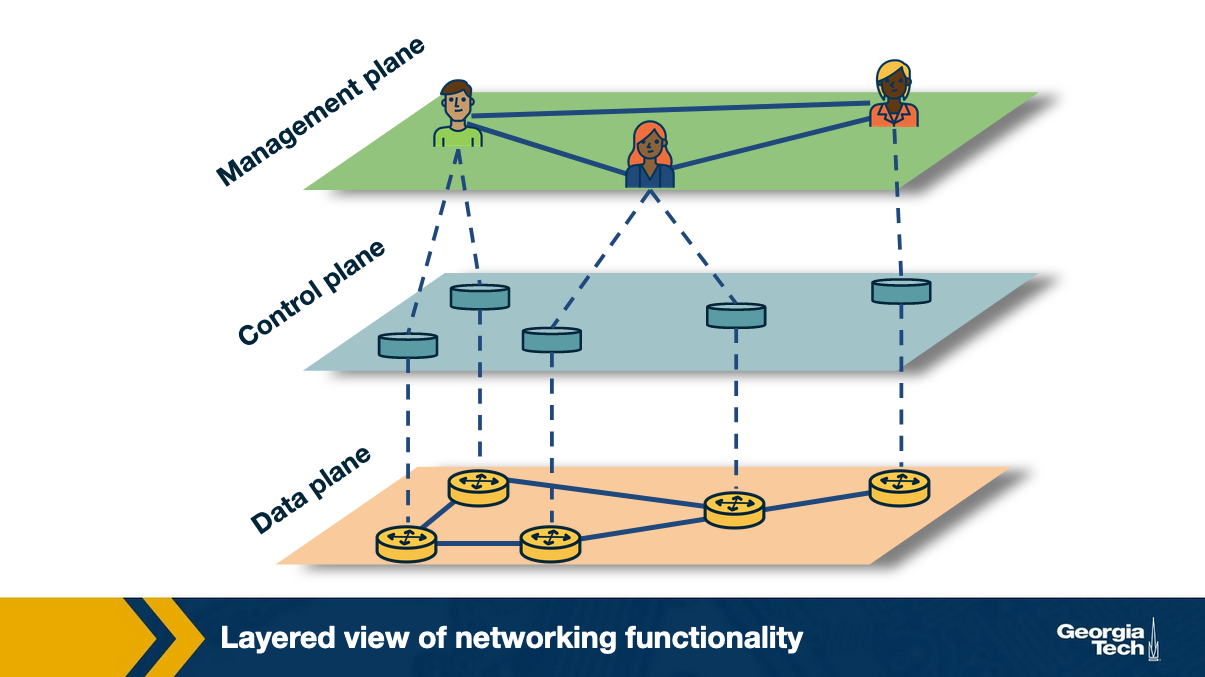

Traditionally viewed, computer networks have three planes of functionality, which are all abstract logical concepts:

Data plane: These are functions and processes that forward data in the form of packets or frames.

Control plane: These refer to functions and processes that determine which path to use by using protocols to populate forwarding tables of data plane elements.

Management plane: These are services that are used to monitor and configure the control functionality, e.g. SNMP-based tools.

In short, say if a network policy is defined in the management plane, the control plane enforces the policy and the data plane executes the policy by forwarding the data accordingly.

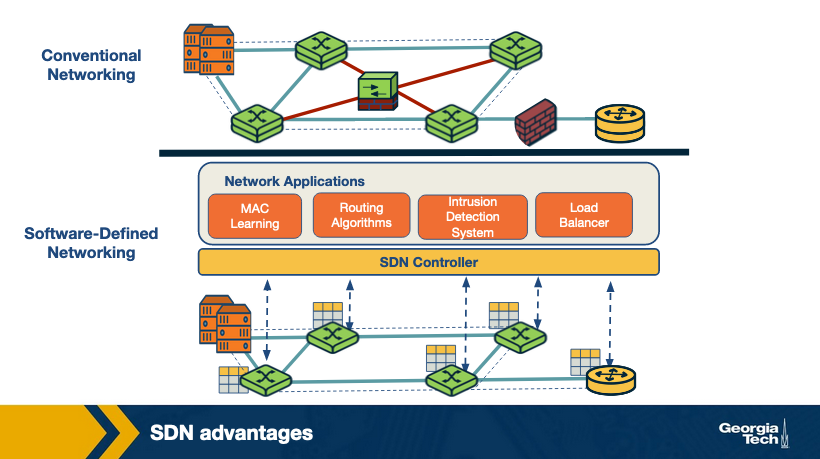

SDN Advantages

What are the main differences between the traditional approach (conventional networks) and the new SDN paradigm? Since the two approaches have contrasting differences, what are the advantages to using the SDN technology?

Conventional networks: We saw earlier that these networks come with a tightly coupled data and control plane, thereby making the networking components physically embedded. As a result, to add a new networking feature, one has to go through the process of modifying all control plane devices - e.g. installing new firmware / hardware upgrades. To avoid this, traditionally, a new specialized equipment was introduced (known as middlebox) through which concepts and features such as load balancers, intrusion detection systems, firewalls, etc. were introduced. Since these middleboxes are required to be carefully placed in the network topology, it is much harder to later change or reconfigure them.

Software-defined networks: Since SDN decouples the control plane from the physical networking devices, it isolates itself as an external entity (SDN controller). With this, middlebox services can be viewed as a SDN controller application. This approach has several advantages:

- Shared abstractions: These middlebox services (or network functionalities) can be programmed easily now that the abstractions provided by the control platform and network programming languages can be shared.

- Consistency of same network information: All network applications have the same global network information view, leading to consistent policy decisions while reusing control plane modules

- Locality of functionality placement: Previously, the location of middleboxes was a strategic decision and big constraint. However, in this model, the middlebox applications can take actions from anywhere in the network.

- Simpler integration: Integrations of networking applications are smoother. For example, load balancing and routing applications can be combined sequentially.